What Animals Did The English Bring Over What Animals Did The English Bring Over

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Animals played a central role in the British Empire. Sources of nutrient and labor, animals symbolized the power of the empire. They besides hindered the efforts of the British to control colonized lands, and they destroyed ecosystems.

A new book examines their relationships with imperial authorities and colonists through essays virtually 26 animals – one for each letter of the alphabet, from Ape and Boar to Yak and Zebu – and how those human-animal relationships reflect on the empire'southward presumption of racial supremacy. "Animalia: An Anti-Imperial Bestiary for Our Times" was co-edited by Antoinette Burton, the director of the Humanities Inquiry Institute and a history professor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Burton contributed two essays.

"Animalia" offers a counternarrative of empire in examining the disruptive forcefulness that animals presented to imperial expansion. Burton and co-editor Renisa Mawani, a folklore professor at the University of British Columbia, wrote in the book'due south introduction that animals "did pose recurrent challenges to modern British imperialism, interrupting the all-time-made plans and reminding would-be colonizers on a regular footing that the terrains they sought to conquer were not uninhabited just were populated both past humans and by unruly fauna species that refused to go away."

The volume connects critical race studies and animal studies in looking at human-animal relations and how racial assertions of supremacy played out in animal form. British imperialists coming into a new environs expected to be the ascendant species and to impose their will on native populations and native fauna species, Burton said.

"You tin't disentangle white supremacy from species supremacy," she said. "There was a lot of white supremacist violence happening in the British Empire. Just some of that was being thwarted in small, ordinary ways by animals. Some of them are quite spectacular examples of how the fauna world worked against the empire."

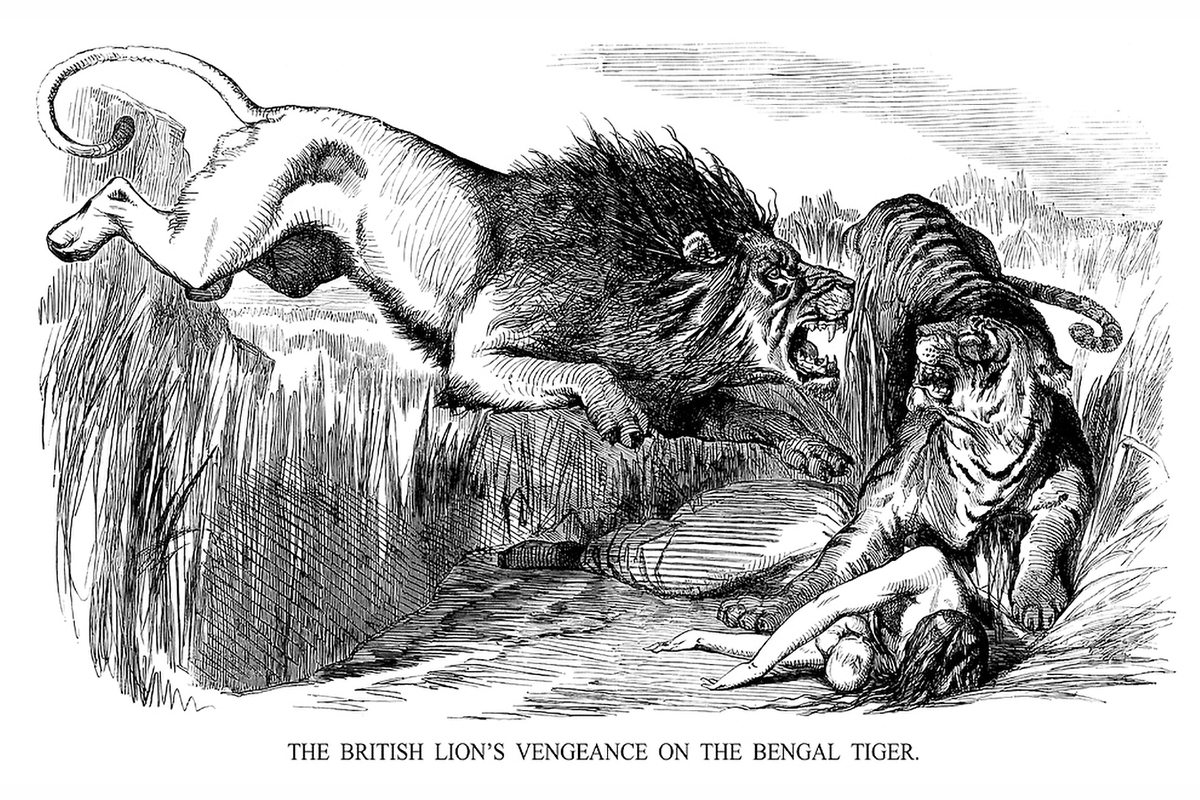

The lion has long symbolized the British monarchy, and its iconography often features a lion wearing a crown or holding a scepter, Burton wrote in her essay "50 is for Lion."

"The lion conjured 'might is right' by linking imperial ability with the hierarchy of natural law in the animal kingdom," she wrote.

Panthera leo hunting became associated with coming of age for certain white men. Burton recounted the story of the homo-eating lions of Tsavo, Kenya, that were attacking laborers on a railway project earlier being killed by a British railway engineer with the help of his local scout. A fictionalized account of the story appeared in the 1996 moving picture "The Ghost and the Darkness."

"Intended every bit a tale of derring-practise, 'The Man-Eaters of Tsavo' also tells stories of struggle, reversal, most failure and one minor, fleeting win for the lion population," as one lioness escapes being killed, she wrote.

Mosquitoes that transmit malaria and yellowish fever were seen as "tiny, mobile threats to a British sovereignty," and mosquito control was considered necessary for expanding colonial development. The British devoted pregnant resources to controlling the transmission of parasites and viruses via mosquitoes, while Indigenous people and enslaved Africans took advantage of their amnesty to yellow fever to challenge colonial rule, according to the book'due south essay on the insect.

Scorpions were a mutual feature of household life in the British colonies, and they also were used every bit a metaphor for agents of anti-colonial struggle, Burton wrote in her essay on that creature.

"Because of their potentially deadly stings, scorpions were feared and even loathed. They were also seen every bit 'enemies,' 'combatants,' and in some contexts, instruments of war," she wrote. "The scorpion was a commonplace colonial menace that brought all kinds of danger to the doorstep."

The book looks at jackals in southern Africa, which preyed on minor livestock and were made stronger when efforts to eradicate them resulted in more adaptable animals surviving.

Cattle were a source of food and labor, likewise as a symbol of agricultural progress, wealth and status, and domesticity. As Indigenous lands were transformed into grazing lands, cattle functioned as "agents of colonization in their ain right" – a new style to dispossess Ethnic people of their lands and natural resource, according to the essay describing cattle's role in the empire. They initiated processes of deforestation that continue today. British imperial pursuits were among the causes of climatic change, Burton and Mawani wrote.

The style of the volume – an illustrated ABC text – was popular during the Victorian era. Interest in zoology was soaring during that historic period of exploration and conquest, and books celebrating animate being life were plentiful. The format is more than accessible than an academic monologue, Burton said. The essays cantankerous-reference other entries, allowing readers to jump to dissimilar sections and making it easier to find connections between species and geographical locations.

"The grade is different and playful, but the content is deadly serious," Burton said. Every bit the British Empire attempted to legitimize its supremacy through a mastery over animals throughout its territories, "the real story is in the struggle over whether and to what extent such supremacy was actually accomplished."

Source: https://news.illinois.edu/view/6367/666102198

Posted by: fergusonpainarompat1996.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Animals Did The English Bring Over What Animals Did The English Bring Over"

Post a Comment